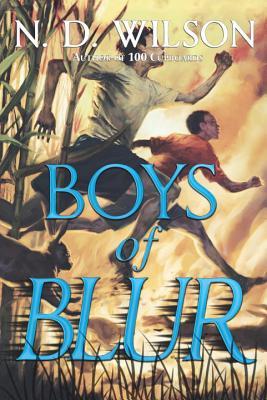

Boys of Blur

Boys of Blur

By N.D. Wilson

Random House Books for Young Readers

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-449-81673-8

Ages 9-12

On shelves April 8th.

I like a kid’s book with ambition. It’s all well and good to write one about magic candy shops or goofy uncles or simpering unicorns or what have you. The world is big and there’s room for every possible conceivable type of book for our children you can imagine. But then you have the children’s book authors that aim higher. Let’s say one wants to write about zombies. Well, that’s easy enough. Zombies battling kids is pretty straightforward stuff. But imagine the chutzpah it would take to take that seemingly innocuous little element and then to add in, oh I dunno, BEOWULF. N.D. Wilson is one of those guys I’ve been watching for a very long time. The kind of guy who started off his career by combining a contemporary tale of underground survival with The Odyssey (Leepike Ridge). In his latest novel, Boys of Blur Wilson steps everything up a notch. You’ve got your aforementioned zombies as well as a paean to small town football, an economy based on sugar cane harvesting, spousal abuse, and rabbit runs. It sounds like a dare, honestly. “I dare you to combine these seemingly disparate elements into a contemporary classic”. The end result is a book that shoots high, misses on occasion, but ultimately comes across as a smart and action packed tale of redemption.

There is muck, then sugarcane, then swamps, then Taper. The town of Taper, to be precise, where 12-year-old Charlie Reynolds has come with his mother, stepfather, and little sister to witness the burial of the local high school football coach. It’s a town filled with secrets and relatives he never knew he had, like homeschooled Cotton, his distant cousin, with whom he shares an instant bond. Together, the two discover a wild man of the swamps accompanied by two panthers and a sword. The reason for the sword becomes infinitely clear when Charlie becomes aware of The Gren. A zombie-like hoard bent on the town’s obliteration (and then THE WORLD!), it’s up to one young boy to seek out the source of the corruption and take her (yes, her) down.

I had to actually look up my Beowulf after reading this. The reason? The opening. Wilson doesn’t go in for the old rules that state that you should begin your book with some kind of gripping slam-bang action scene. His first page? It reads like an ode. Like a minstrel has stepped out of the wings to give praise to the gods and to set the scene for you. Only in this case it’s just the narrator telling you what’s what. “When the sugarcane’s burning and the rabbits are running, look for the boys who are quicker than flame.” Read that line aloud for a second. Just taste and savor what it’s saying. It sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Like you’ve read it somewhere else before (particularly that “look for the” part). Then there’s that last line. “Out here in the flats, when the sugarcane’s burning and the rabbits are running, there can be only quick. There’s quick, and there’s dead.” So I looked up the beginning of Beowulf just to see if, by any chance, Wilson had cribbed some of this from his source material. Not as such. The original text is a bit more concerned with great tribal kings past, and all that jazz. That doesn’t make Wilson’s book any less compelling, though. There’s a rhythm to the opening that sucks you in immediately. It’s not afraid to be beautiful. It begs to be heard from a tongue.

And while I’m on the topic of beautiful language, Wilson sure knows how to turn a phrase. If he has any ultimately defining characteristic as a writer it is his complete and utter lack of fear regarding descriptions. He delves into them. Swims deep into them. Can you blame him? Though a resident of Idaho, here he evokes a Florida that puts Carl Hiaasen to shame. Examples of some of his particularly good lines:

“As for the church bell, it crashed through the floorboards and settled into the soft ground below. It’s still down there, under the patched floor, ringing silence in the muck.”

“Charlie looked at the sky, held up by nothing more than the column of smoke he’d noticed during the service.”

“Charlie stopped at the end, beside a boy with a baby face on a body the size and shape of someone’s front door.”

And I’m particularly fond of this line about new siblings: “When Molly had come, she had turned Charlie into a brother, adding deep loves and loyalties to who he was without asking his permission first.”

The book moves at a rapid clip, but not at the expense of the characters. For one thing, it’s nice not to have to read about a passive hero. From early in the book, we know certain things about Charlie that are to serve him well in the future. As the story says, thanks to experiences with his abusive father, “he could bottle fear. He’d been doing it his whole life.” This gives Wilson’s hero a learned skill that will aid him in the rest of the story. And when there are choices to be made, he makes them. He isn’t some child being taken from place to place. He decides what he should and should not do in any given moment and acts. Sometimes it’s the right choice and sometimes it’s wrong, but it is at least HIS choice each time.

The sugarcane fields themselves are explained a bit late in the narrative. On page 64 or so we finally get an explanation about why the boys are running through burning fields to catch rabbits. For a moment I was reminded of Cynthia Kadohata’s attempts to explain threshing in her otherwise scintillating book The Thing About Luck. Wilson has the advantage of having an outsider in his tale, so it’s perfectly all right for Charlie to ask why the only way to successfully harvest cane is to burn it, “Fastest way to strip the leaves . . . Stalks is so wet, they don’t burn.” Mind you, this could have worked a little earlier in the story, since much of the book requires us to take on faith why the rabbit runs occur.

It’s also an unapologetically masculine story as well. All about swords and fighting and football and dangerous runs into burning sugarcane fields. The football is particularly fascinating. In an age when concussions are becoming big news and people are beginning to turn against the nation’s most violent sport, it’s unique, to say the least, to read a middle grade book where small town football is a way of life. Small town football almost NEVER makes it into books for kids, partly because baseball makes for a better narrative by its very definition. Football’s more difficult to explain. Its terms and turns of phrase haven’t made it into the language of the cultural zeitgeist to the same extent. For an author to not only acknowledge its existence but also give it a thumbs up is almost unheard of. Yet Boys of Blur could not exist without football. Charlie’s father went pro, as did his stepfather. The book begins by burying a coach, and there are long seated animosities in the town behind old high school football rivals. For many small towns, life without football would be untenable. And Boys of Blur acknowledges that to a certain extent.

The women that do appear are few and far between, but they are there. One should take care to note that it’s Wilson’s source material that lacking in the ladies (except for the big bad, of course). And he did go out of his way to add a couple additional females to the line-up. It’s not as if Charlie himself doesn’t notice the lack of ladies as well anyway. At one point he ponders the Gren and wonders why there aren’t any girls. The possible explanation he’s given is that much as a selfish man is envious of his sons, so would a selfish woman find her own daughters to be competition. Take that as you may. We veer close to Caliban country here, but Wilson already has one classic text to draw from. Shakespeare can wait.

Charlie’s mother would be one other example of a woman introduced to this story that gets a fair amount of page time. On paper you’d assume she was just a victim, a woman who continues to fear her ex-husband. But in reality, Wilson gives her much more credit. She’s the woman who dared to get out of an untenable situation for the sake of her child. A woman who managed to find another husband who wasn’t a carbon copy of the first and who has done everything in her power to protect her children in the wake of her ex-husband’s threats. And most interesting, Wilson will keep cutting back to her in the narrative. He doesn’t have to. There’s a reason most children’s fantasy novels star orphans. Include the parents and there’s a lot of emotional baggage to attend to. But Wilson’s never liked the notion of orphans much, so when his story cuts back to Natalie Mack and what she’s up to it’s a choice you go along with. In Wilson’s books parents aren’t enemies but allies. It goes against the grain of the usual narratives, wakes you up, and makes for better books.

Where do heroes find their courage and resolve? In previous books Wilson had already gone underground and into deep dark places. In Boys of Blur he explores the dual worlds of cane and swamp alike. Most epic narratives of the children’s fantasy sort are long, bloated affairs. They feel like they can’t tell their tales in anything less than 300 pages, and even then they end up being the first in a series. Wilson’s slick, sleek editing puts the bloat to shame. Clocking in at a handsome 208 pages it’s not going to be understood by every child reader. It doesn’t try for that either. Really, it can only be read by the right reader. The one that’s outgrown Harry Potter and Percy Jackson. The one who isn’t scared off by The Golden Compass and who will inform the librarian that they can’t possibly impress him or her because they’ve read “everything”. This is a book to stretch the muscles in that child’s brains. To make them appreciate the language of a tale as much as the action. And yes, there are big smelly zombies that go about killing people so win-win, right? Some may say the book ends too quickly. Some will wonder why there isn’t a sequel. But many will be impressed by what Wilson’s willing to shoot for here. Like the boys in the cane, this book speeds out of the gate, quick on its feet, willing to skip and hop and jump as fast as possible to get you where you need to go. If you’ve read too much of the same old, same old, this is one children’s book that’s like no other you know out there. Gripping.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from author for review.

Like This? Then Try:

- Zombie Baseball Beatdown by Paolo Bacigalupi – Lots of similarities, actually. Particularly when it comes to beating down zombies in cane fields / corn fields.

- Beowulf by Gareth Hinds – Undoubtedly the best version of Beowulf for kids out there, this is Hinds’ masterpiece and is not to be missed.

- The House of Dies Drear by Virginia Hamilton – Bear with me here. It makes sense. In both books you’ve mysterious African-American men hiding a secret of the past, scaring the local kids. I draw my connections where I can.

First Line: “When the sugarcane’s burning and the rabbits are running, look for the boys who are quicker than flame.”

Other Blog Reviews:

- Random Musings of a Bibliophile

- Librarian of Snark

- Pages Unbound

- Books and Movies

- Good Books, Good Wine

- Fiction State of Mind

Misc: Read some of the book yourself to get a taste.

Videos:

Remember, if you will, that Wilson both shot and narrated the following book trailer. One of the best of the year, too: